The Calm Calculus of Reason (Pt. 2 of 9)

A Conversation with Frank Lisciandro

By Steven P. Wheeler

In Part 2, Frank and I discuss the early days of The Doors, the band’s first gig on the Sunset Strip, working on the group’s 1968 documentary Feast of Friends, and filming the Hollywood Bowl concert.

THE OPENING OF THE DOORS

Ironically, by 1965, Ray and Jim had formed a band called the Doors. Were you around them at that time?

That was a great summer. I was hanging out at the film school and I was hanging out with friends in Venice. Ray had a house there, so I’d go and watch them rehearse sometimes because we were still hanging around that summer.

And later I saw the Doors at their very first performance on the Sunset Strip, I think it was the early part of ’66. All of the film students went to the London Fog on that first night.

And what was your initial impression of them onstage?

Well, I thought Jim was terrible. For the most part, he was still pretty darn shy, so he kept his back to the audience; he really did. I just didn’t think he could sing very well. Shows you how much I know about discovering new musical talent [laughs].

A few years later, after we became friends, I told Jim about my first impression of him at that first show, and I said, “I thought you were terrible that night.” I remember he gave me a look that seemed to suggest that he didn’t like the word “terrible” [laughs].

But then I told him he had improved tremendously and that he was like a Frank Sinatra crooner who could also sing rock, and I asked him, “What changed?” He just said, “I just kept practicing and I kept practicing, practicing, practicing.” And obviously he had been doing something to improve. If you listen to their first demo and then their first album, there is such a difference and you can hear it. But they rehearsed a lot and they played a lot, too. I guess you can’t really help but improve if there’s the will and the talent, right?

But before the band became stars, you and Kathy went off to Africa with the Peace Corps, right?

Yeah, but before we went off to Africa, we spent four months in Peace Corps training, and by late ’66, we were back in New York for a few weeks before we would head off to Africa, and the Doors were playing at Ondine’s in New York City.

We invited Ray and Dorothy to have dinner with us at Kathy’s parents house and then we went with them to Manhattan and saw one of the shows at Ondine’s. And from what I saw that night, Jim had already improved a great deal. I could see that this was a whole lot better than what I saw at the London Fog.

Jim had the full-on rocker guy thing going, but you could tell that he had been drinking or that he was on drugs or something, because he was kind of erratic at that performance. They put on a good show though and the audience seemed to like them, and we were delighted that we got to see them at a really nice club, and then we were off to Africa.

Even though you saw the improvement in Jim’s performance that night, did you have any sense that he was soon going to be a superstar?

No! Not at all. But while we were in Africa, Ray sent us a press clipping about the band because we were corresponding with him while we were there. So we were kind of astounded to read this press clipping talking about their first album and “Light My Fire” being a Number One hit. We couldn’t believe it.

I assume because of your friendship with Ray and Jim that you eventually became a big fan of the band though…

Well, let me say that I appreciated their music, but I was not a confirmed fan. I wasn’t secretive about it or anything. I was pretty open about Dylan being a demagogue to me, and that there were other bands and artists I was much more into. I liked a lot of the Doors’ music, but I just had different musical tastes.

When did you realize that the Doors had really broken through in a big way?

After a year in Africa, we were ready to come home. We went from Togo to France where we stayed for about a month before we came back to the States. I was looking for a job in the French film industry. And one day, we were walking down the Boul Mich and we saw the Strange Days album in a record store; must have been sometime in the later part of ’67. We were thrilled for them, especially for Ray, who we considered to be a close friend.

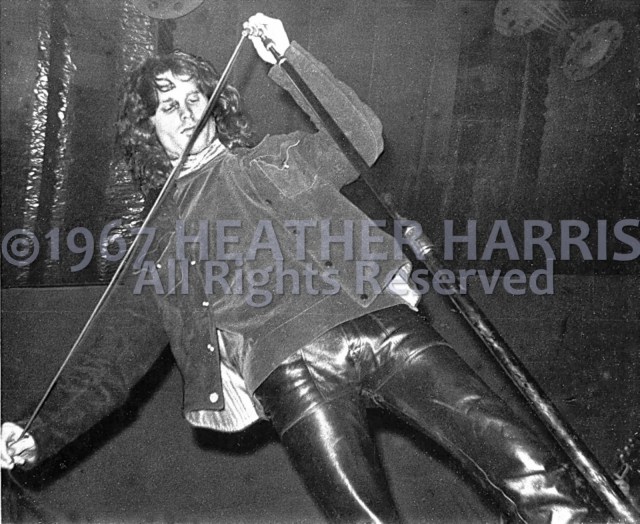

Anyway, we came back to California and found an apartment in Santa Monica, got in touch with Ray and Dorothy, and we went to see the Doors at The Shrine Auditorium; must have been at the end of ’67. That might have been the first time that I photographed the band onstage. I had my camera with me and started taking pictures. And that’s the first time that I saw that they were a big American band. They had top billing that night [over the Grateful Dead], and there was a light show going on and it was really cool.

Meanwhile, around that time, a friend of mine who was at the film school with me, Jim Kennedy, had managed to get a job at a production company and he got me a job there, too.

FEAST OF FRIENDS

So you were working as a film editor, but at what point did you get professionally involved with the Doors?

The first real job I had with them—the first real paying job with the Doors—was when Paul Ferrara asked me to be one of the camera operators at the Hollywood Bowl concert which was in July of 1968. Paul had been shooting stuff on tour for several months for what was to become the Feast Of Friends documentary, and the Hollywood Bowl concert was to be the culmination of all that.

Is that the beginning of how you ultimately got involved with the documentary?

I probably was the only guy that they knew from film school who was actually working in the film industry at that time. So they asked me to come down and look at all the footage, and asked me what I thought.

Then Ray asked me if I would consider editing it all, because that’s what I was at that time; a film editor. I’m sure Paul could have done it, but Paul was busy shooting both stills and film for the band and he was busy with his acting career; so he was probably too busy to sit down and really focus on editing a documentary.

What was your first reaction to all the footage that you were presented with? Was there any semblance of what they were wanting to do with it all?

They shot all this footage, but there was no form or rhyme or reason to it all. So they asked me to try putting it all together and I gave up my day-job to do it, because they had an enormous amount of footage to get through. And back then, you were dealing with 16mm film; so it was a very hands-on process that took hours and hours to do.

I just had to go through everything from scratch and organize it all, and find out where the negative was, then put together a work-print from the neg, and then synch up the work-print, which is a tough enough job, but it’s really tough when things aren’t shot with a slate. You have to eyeball it and that took a tremendous amount of time in those days; even today, it takes time.

What we had was a lot of footage where Paul and Babe Hill were just shooting things. Paul knew what he was doing, he was really good at shooting, but they wouldn’t give him any money to hire anybody else and that’s how Babe got pulled into it, because he was Paul’s friend from high school.

So Paul showed Babe how to use the Nagra tape recorder and he went around collecting sound; sometimes it was synched, sometimes it wasn’t. What I ultimately had to work with was a very large and interesting collection of very dynamic images and scenes that didn’t seem to have any solid core or theme.

But when you were brought into the project, they had to have given you some sort of overall philosophy or direction of what the resulting film was supposed to be, no?

It was supposedly a film about the Doors in America. It didn’t even have a title at that time. They had a moviola machine for editing in the backroom of the Doors rehearsal studio; what would later become known as the Doors Workshop, where Vince Treanor was busy making these monolithic sound systems by hand.

So they hired me to edit all that footage into something, and I was put on the Doors payroll and began working on Feast Of Friends, and it was at that time that I began doing more photography of them as well.

Was there room for you to do any photography, since Paul was already doing that for the Doors?

Paul was doing fabulous photography for the Doors, including the album cover for Waiting For The Sun. Paul and I were friends from back at UCLA, and we were closer back then because in addition to the film school, we both took photography classes through the Art Department at UCLA, and were in the same class together for two semesters.

So I think Paul enjoyed having me there, because he knew me and I wasn’t someone from the outside, and he knew I could do what they needed me to do. He also knew that I could shoot film and photos, but maybe Paul was kind of protective of the “stills” stuff when it came to the Doors, because he knew that photography was my strong suit and he never really encouraged me to do any photography with the Doors if he was around [laughs].

Back to the Feast Of Friends documentary. So you’re saying that there was no outline or plan for the film when you began the editing process?

I never saw an outline, I never saw a plan, I never saw anything written down. If there was one, it was completely out the window by the time I came on the scene [laughs].

With that said, there are two ways to make a documentary film. There’s the gathering of the evidence, but you can do that without a formal plan. I mean, it doesn’t look like D.A. Pennebaker had much of a plan when he did the Dylan film [Don’t Look Back]. He went to London with Dylan, but he didn’t know what was gonna happen. He brought back the footage and put it all together.

Then there’s the other kind of documentary film, where it’s somewhat scripted to where you have an overall sense of where you’re going to go with it. So there are different ways to approach it, and each are equally acceptable.

But, in answer to your question, no, I never saw any kind of outline or plan, and certainly when I was putting it together, everything was open. I mean Paul and I literally invented scenes, based on the footage, or lack thereof. I’d say, “Look how these shots work together,” and he’d say, “Let’s add this.” So, yes, we collaborated at the beginning of the editing, but Paul was busy with other stuff; he was wanting to be an actor and had an agent and was going on these road trips with the Doors. He just had multiple things going on at the time.

Did you ever get a sense of how the seeds of that film project were planted?

When it comes to Feast Of Friends, I think that Paul had kind of enthused the Doors into doing this project. It was Paul’s enthusiasm about it, and the fact that both Ray and Jim were interested in film and had some money to do something about it. So Paul got to be the filmmaker, and he brought me in to try and put it all together as a creative film editor.

Despite the randomness and incomplete footage you had to work with, there are some amazing scenes and sequences that were shot and put together. Can you go through any of the thought process that you went through during the editing?

Well, for instance, there’s the sequence for “Moonlight Drive” which came about because I just loved how so many of the shots were in shadow; heavily shadowed with spotlights. So I began gathering all those types of images together from the various concerts and started putting it all together with the song, because we didn’t have a soundtrack.

What about Jim’s involvement in the project? Did he show much interest or get involved with the editing process?

Jim was embracing everything about Feast Of Friends. He was enthused about it, he was helpful and he enjoyed watching things when I was cutting it. He wouldn’t have made a good editor though, because he could find something to like in almost every shot. Like when we were working on HWY, it was hard to cut things out because he liked everything [laughs].

But Jim would see things that I didn’t see sometimes, and he’d point things out to me. He would make suggestions, especially when it came to the nuances of a song that was being used. Like with the “Moonlight Drive” sequence, he would say, “No, the rhythm of the song is too fast, you need to speed up the images to match it.”

Did he come to me with full ideas for scenes or anything like that? No. But he did have a real interest in what I was doing and what the ultimate result was going to be. I also think his overview of the project itself was different than mine. I think his idea was that we would release this film and it would get to an audience that had never seen a Doors concert before. We did have the hope that it would be shown at some film festivals and maybe on PBS, and that it would help promote the band, and Jim was definitely onboard with that.

THE HOLLYWOOD BOWL

There seems to be this idea that Feast Of Friends had this huge budget behind it, but with the multi-camera set-up and sound recording that was involved with the Hollywood Bowl concert, one would think that maybe 70-75% of the entire budget was blown on just that one single concert?

I think you’re about right, but I wouldn’t say “blown”. The Hollywood Bowl show was the only time we had sync-sound for the entire concert, because Elektra had the mobile recording truck there. Paul [Ferrara] and I were the two main cameramen, and they hired three other people to shoot from three other cameras; one of which was a slo-mo camera.

One of those other cameramen was Harrison Ford, right?

No. I seem to remember that he was involved; he might have been a film-loader, but not a cameraman.

The shoot at the Bowl was a very stressful experience. We had to deal with the regulations of the Bowl in terms of filming, Elektra had their recording truck there to make sure all the sound was working, so I was pretty focused on what I needed to do which was to shoot 16mm film, and try to shoot a few stills which I also did.

My camera was the one right in front of the stage to Jim’s left. So much of what people have seen of that concert came from my camera; all those close-up and profiles of Jim at the microphone.

The big problem was that Paul’s camera wasn’t in sync all the time, and he had the best vantage point. He was squarely in the front-center shooting straight down to the stage, so he could cover the whole stage. Whereas my job was to shoot Jim in medium close-up and follow him around, and shoot Ray and Robbie whenever I could. But Jim stayed at the microphone pretty much the whole time that night, so I didn’t have to try and follow him, except when he danced and I’d pull-out to a wide angle and try to keep him in view.

What did you think of their performance that night?

Do I think they gave a good performance that night? I have no idea, because I didn’t see it, ya know what I mean? I was so focused on what I was doing that the whole night was a blur. But that always happens, even when I’m just shooting stills at a concert, you’re so in the moment of what you’re doing, you can be oblivious to the bigger picture, so to speak.

The major criticism about Feast Of Friends coming from a new generation of fans seems to center on the fact that, other than the Hollywood Bowl performance of “The End,” there were no full performances in the film…

Well, that’s because it wasn’t a concert film and was never supposed to be. I remember talking to Ray and Paul—this is before Jim got involved at the editing stage—and they were saying that the film was about “The Doors in America in the Sixties during the time of upheaval, revolution, war,” and all of that stuff. That’s what the film was supposed to be about.

And it starts out with the Hells Angels following this limousine with a long-haired guy inside of it who has the Hells Angels as bodyguards. He’s like a rebel leader in that sense, and then you have the limo arrive somewhere and a girl reaches in the window and grabs the crotch of this new leader. I mean the irony and the absurdity of that juxtaposition of realities was very appealing to me [laughs].

But, look, I only had the footage to work with that I had to work with. I did put the voiceover of the guy talking about the Vietnam War during the scene where the band is on the monorail. That was an attempt to put them in the midst of the Vietnam War, but I’m not so sure that people even got that, but that’s what that was about.

My thought was that it was the Doors in America in the Sixties, so that’s what I tried to do, but it reached a point where the Doors didn’t want to spend any more money on the film, and then it came down to the producer’s bottom line, “try to put it together as soon as possible and we’re done.”

Did you ever approach them about trying to flesh it out with additional footage?

Well, I put my ideas on the table, whether through talking with Ray or Jim or Paul; I think I came up with the name of the film, Feast Of Friends.

But you have to realize that, at the time, these guys were the Number One band in America; they had other things on their mind. This film was a very, very small part of what was going on with them. They didn’t have time to spend on this little documentary film. I mean, Ray would pop in every now and then and look at a scene, but after the Hollywood Bowl was shot, I don’t think any cameras were turned on again.

What about the amount of footage that hasn’t been seen. Outside the fifteen-minute Hollywood Bowl performance of “The End” at the end of the film, that leaves about 30 minutes of footage that was used. Any estimates on how much overall footage exists?

Other than the Hollywood Bowl footage, I would estimate that we used a ratio of about 8-to-1 or 10-to-1.

So maybe four hours of footage that wasn’t used at the time for “Feast”, but probably most of that footage has been re-purposed over the years, including actual scenes you cut for “Feast”…

I like that word, “re-purposed” [laughs]. I don’t know how much was used in those video projects. People have sent ‘em to me, but I don’t look at them. From what little I have seen there are definitely shots from Feast Of Friends and they are cut together in ways that don’t have any context.

Then again, Ray’s a better filmmaker than that, so I suppose if I were to sit down and look at those video projects without prejudice, I’d probably find them to have a little more coherence. I will say that, at one point in the past, I got a little pissed off about not getting credited for any of the work that I did or for the scenes that I had originally put together for Feast that were appearing in other videos without any credit to me.

“I can remember that day as clearly as any from those days. Jim stood there listening to us present our case, and in the end told us to go ahead and complete [Feast of Friends]. He would handle the other guys in the band.”

As for the film itself, what is your most objective take on Feast Of Friends?

I haven’t seen it in at least a half-dozen years and it’s hard to take yourself totally out of the equation and look at it from a completely objective point of view. Surely, it could have been a better film. Certainly, it could have had a little bit more cohesion.

Then again, with Feast Of Friends, we were trying to use new forms of filmmaking and that was certainly one of the reasons that we structured it without a beginning, middle and end. It was supposed to be a visual representation of the Doors in America in a way that reflected the Doors music, which was anything but ordinary from a musical standpoint.

Sure it could have been a better film if it had a bit more budget and if it had a little more organization and planning done at the beginning perhaps. But that’s all hindsight. Paul was carrying all the weight of that project on his shoulders until I came along and I think he was more than willing to pass some of that weight onto my shoulders. I think he needed to have someone else involved on a professional level.

By the time Jim got involved and showed an interest in the film and became somewhat protective of it, the guys in the band were seeing that they had spent $40,000 on it and decided they didn’t want to put any more money into it; and that was almost the end of the creative process, because they wanted to pull the plug and leave the film unfinished.

In the end, Paul and I went to Jim and asked that we be given enough money to finish the editing and do a sound mix and at least make a release print. I can remember that day as clearly as any from those days. Jim stood there listening to us present our case, and in the end told us to go ahead and complete the project. He would handle the other guys in the band.

Sticking with the film stuff for a minute, there are stories of Jim being courted by the Hollywood industry, but that he torpedoed any chance of that by alienating producers, directors, agents and actors with a cocky attitude towards filmmaking that many Hollywood veterans felt he had yet to prove…

I just didn’t see that type of behavior from Jim in those situations. Jim was much more passive than actively hostile to people. So rather than become abusive or cop an attitude, he’d get drunk and screw it up that way. And that was his way of ducking out of situations that frustrated him.

I think he had a problem with authority and perhaps people with strong fathers do. That’s one of the things Jim and I had in common; we both had strong fathers. So we both shared this kind of On The Road attitude about authority figures.

The Calm Calculus of Reason – Pt. 3

Jim Morrison: Friends Gathered Together

Print Edition Available Now on Amazon, as well as all ebook platforms

12 Replies to “The Calm Calculus of Reason (Pt. 2 of 9)”

546204 525616This is a good blog. Keep up all the work. I too adore to blog. This is wonderful everyone sharing opinions 60571

Thanks for the comment, cheers 🙂

Hi there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

Definitely don’t use Twitter, but you can always find me on Facebook. Cheers…

740818 881802Enjoyed reading by way of this, extremely good stuff, thankyou . 233723

Thanks Melody, appreciate the comment 🙂

Hello. fantastic job. I did not imagine this. This is a great story. Thanks!

Thanks Raul… much appreciated 🙂

Hi there would you mind stating which blog platform you’re working with? I’m going to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a hard time choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S My apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

Which one do you prefer?

15728 186479An incredibly fascinating read, I may possibly not concur completely, but you do make some really valid points. 391999

Anything in particular you disagree with?